When Anna Jackson was first diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, her body was signaling a profound struggle within.

“My hair was falling out, my eyes were sunken in, and I was so undernourished that if I stood up, I’d pass out,” Jackson said. “I had to undergo re-feeding because my bones were eating themselves.”

Like 70% of people with anorexia, Jackson has comorbid conditions, citing her depression and anxiety as the underlying causes of her eating disorder.

“I started having really bad anxiety and panic attacks and depression, to the point that I was diagnosed with agoraphobia. I couldn’t even get out of bed without having a panic attack. The only thing that I could find within my realm and find some sort of control was what I could eat.”

Between 2017 and 2022, Jackson was admitted to the hospital 10 times, in facilities across four states that could provide the necessary care for anorexia. Despite the severity of the illness, which is the second most fatal mental health condition outside of opioid use disorder, accessing sustainable insurance coverage was a challenge.

“You often have to go on a week-to-week basis, where you resubmit a claim and send out your medical documentation, and insurers can make the decision that tomorrow’s your last day.” she said. “I had to scramble with the logistics, and most concerning, I faced enormous stress about my health and wellbeing. A lower level of care can increase relapse, so I was back at square one, planning the next step.”

Caption: Hospitalization at the Eating Recovery Center in Denver, Colorado

Like many mental health conditions, treatment for anorexia is complex, and weight is often the primary — and sometimes sole — factor used by plans when considering the medical necessity of coverage. The American Psychiatric Association has outlined a range of guidelines for care, which may include weight alongside medical status, suicidality, and other attendant disorders.

“It’s quite difficult to continue to get coverage for eating disorders when you’re in a treatment program where you are re-feeding,” she said. “Ultimately that kept leading to my relapse because I was in no way near stabilization and recovery, but because my weight had improved, in insurance’s eyes I was deemed stable. Even if I had ample psychiatric documentation saying, ‘you cannot release her.’”

Ultimately, Jackson was able to achieve recovery when she found a care team that treated her condition comprehensively. Major organizations like the National Alliance for Eating Disorders often call for specialized teams, which may include a primary care physician, a dietician, a therapist, and others.

Jackson’s dietician is a specialist in anorexia and provides a range of services that have helped support recovery. For instance, Jackson has a weightless scale that sends her weight to the practitioner. If there’s a downward trend, her dietician may check in.

“I can confidently say she is the reason I have not relapsed.”

Caption: Graduation day after months of residential and partial hospitalization treatment at Eating Recovery Center in Denver, Colorado

Unfortunately, insurance limits Jackson’s treatment due to how it is coded in their system, not as a mental health condition, but relating to diet and weight.

“Even though according to the World Health Organization anorexia is a mental illness and it stems from mental illness, my insurance won’t cover anything because it’s considered ‘obesity counseling.’”

Jackson considers herself lucky. Her family and husband have supported her journey—financially and emotionally — but she understands that many people will not get the treatment they need.

Eating disorders affect people across background, geography, gender, body type, veteran status, and profession, yet less than 20% of people ever get proper treatment, with cost remaining a significant barrier to care. The average inpatient stay costs approximately $20,000 according to a 2024 study.

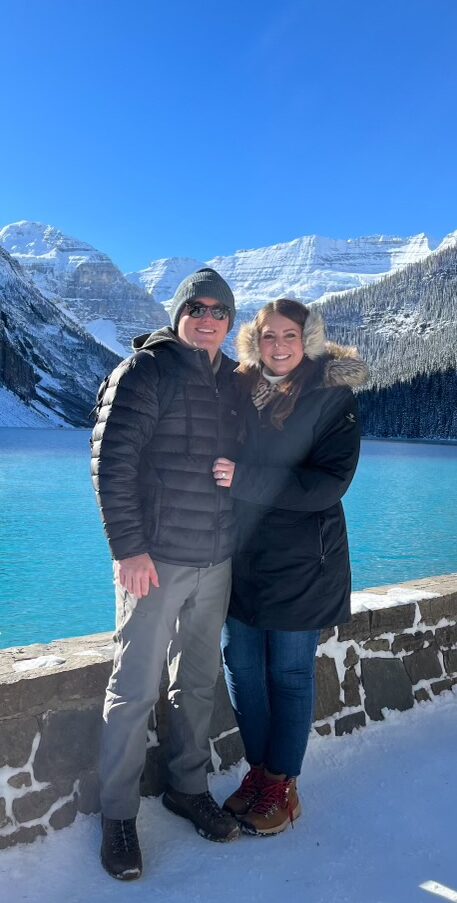

Caption: Jackson completed a bucket list item – visiting 30 countries in 30 years. “I didn’t think I would accomplish it based on my health history.”

“I’m extremely passionate about having equitable patient access and coverage,” she said. “I started documenting everything in interactions with my insurance company in the hopes that it would have some kind of domino effect for other people to have access.”

Despite a grueling effort to get coverage with support from her care team, Jackson’s appeal process is exhausted. She is currently paying thousands of dollars for care, but remains in recovery. She has founded a patient advisory board for Emory Health Care to be able to advance education and destigmatize certain conditions like anorexia.

She is now adding her voice to many like her who have experienced the same gaps in mental health parity. “We have all just put in so much time to say, this is wrong. You’re not providing equitable care. It has to change.”

Have you been denied coverage for your mental health? Please email info@thekennedyforum.org if you’d like to share your story. To learn more about improvements in mental health parity federally and in states, please follow The Kennedy Forum on LinkedIn, to see how we are advancing and defending mental health parity.